Unit Economics of a Niche Workshop: How to Make Church Woodcarving a Sustainable Business

— “Unit economics is the language that allows honest answers to whether each project generates profit considering all costs, not just materials.”

Introduction: Why unit economics matters even for crafts

In craft environments, discussions about numbers are often seen as secondary: the priority is “to make beautiful work and do it conscientiously.” This mindset is understandable, but it often leads to workshops with high artistic standards living from one advance payment to another, failing to build reserves, and relying on one or two large orders.

Unit economics is the language that allows honest answers to several key questions:

-

Does each project generate profit considering all costs, not just materials?

-

Which types of work are more profitable, and which should be limited?

-

What are the limits for discounts or “special conditions”?

-

What is the minimum number of projects per year needed for the business not only to survive but to grow?

For a full-cycle church woodcarving workshop (concept, 3D model, working documentation, production, installation), understanding these parameters is critical: the cost of errors in project timelines or budget is much higher than in a household furniture niche.

1. Defining the unit in a church woodcarving workshop

The first step in working with unit economics is defining the unit itself. In mass-market business, this could be an order, subscription, or transaction. In a high-artistry craft workshop, it is more logical to think in multiple levels:

-

Project unit — one completed project (e.g., a full iconostasis or a complex interior ensemble for a church).

-

Functional unit — a major block within the project (central tier of the iconostasis, side panels, kiots, analogs).

-

Time unit — one person-hour of work by a carver, joiner, or designer.

At the strategic level, analysis is conducted by projects and types of work, while operational management focuses on person-hours and workshop utilization.

It is important not to consider only the cost of materials and labor. Unit economics calculations should include:

-

Direct materials (wood, adhesives, coatings, hardware);

-

Direct labor (hours of carvers, joiners, designers, installers);

-

Share of fixed costs (rent, equipment depreciation, taxes, accounting, communications);

-

Administrative and management resources (time spent in negotiations, approvals, and travel).

Only by accounting for all these components can the profitability of each project be honestly assessed.

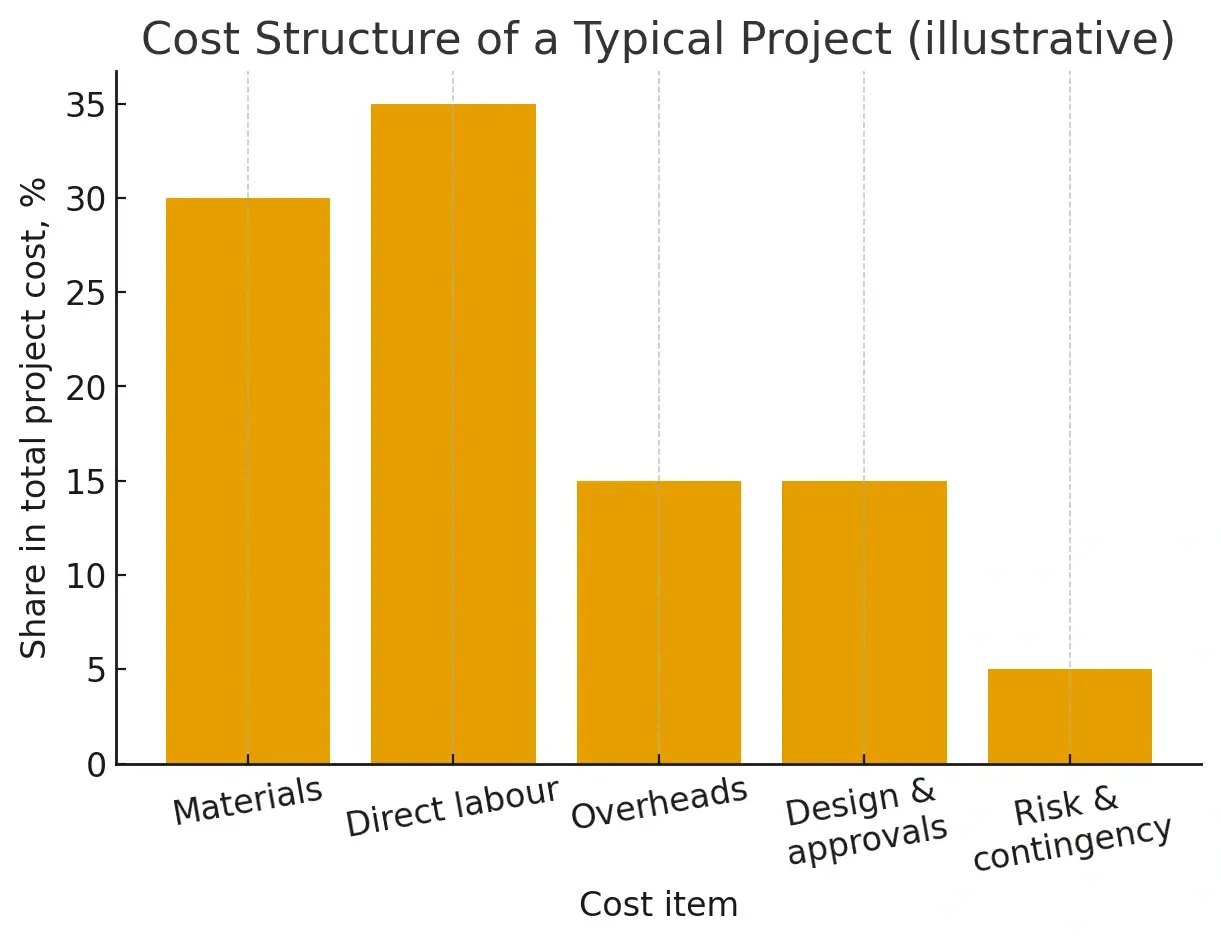

2. Cost structure: where the workshop’s money “hides”

Experience shows that a major mistake of craft workshops is underestimating fixed and “invisible” costs.

a) Materials and direct labor

This part is usually relatively controlled: wood purchases are tracked, workshop labor hours are recorded, and expenses for coatings and hardware are accounted for.

b) Fixed costs

Rent, utilities, machine maintenance, insurance, taxes, accounting—all these must be allocated to projects proportionally to their duration and labor intensity.

c) Design and approvals

In the church field, a significant amount of time is spent on:

-

site visits for measurements and discussions with the rector;

-

development of sketches and 3D models;

-

adjustments based on feedback;

-

preparation of documentation for approvals by church authorities.

If these hours are not included in the calculations, the workshop inevitably “gives away” part of its work for free.

d) Risks and contingencies

Delays in material delivery, rising material costs, additional site visits, and rework of individual elements—all of these should be factored into the model as a cautious allowance for unforeseen expenses (for example, 5–10% of the budget).

3. Pricing: from “market intuition” to a clear formula

In niche craft businesses, pricing is often set “by feel”: “this is roughly what work of this level would cost locally.” Intuitive understanding of value is important, but it must always be supported by calculations.

A basic pricing approach includes:

a) Calculating the full cost of the project

This includes all types of expenses listed above.

b) Defining the target margin

For example, the workshop sets a minimum gross margin per project, which must not fall below a certain percentage.

c) Market validation of the price

Prices are compared with similar workshops (through publicly available information or informal contacts) and with the willingness of the target audience to pay.

d) Setting payment terms

Staged payments (advance, design payment, interim payments upon completion of project blocks, final settlement) simplify cash flow management and reduce the risk of shortfalls.

This forms a clear formula:

Project price = full cost + target margin,

while taking into account risks and market constraints.

4. Project portfolio and revenue: why it’s important to look at the year as a whole

Unit economics is not limited to analyzing a single project. It is important to see the overall picture over the course of a year:

-

how many projects of different types the workshop can execute simultaneously;

-

how the workload is distributed across months;

-

how cash flows align with the production and installation schedule.

Several types of projects can be conditionally distinguished:

-

Large iconostases and complex interiors (high revenue, high workload, long cycle)

-

Medium projects (partial iconostasis, several kiots, panels)

-

Small forms (individual elements, rework, repairs, small orders)

A balanced portfolio contains a combination of these components. Large projects generate the bulk of revenue, while small ones smooth cash gaps, keep the workshop engaged during gaps, and maintain relationships with various parishes.

When planning for the year, it is important to:

-

avoid over-concentration on a single mega-project;

-

allocate realistic time reserves for each stage;

-

not count potential revenue from projects that have not yet been formally signed.

5. Digital tools and standardization as profitability factors

From the perspective of unit economics, digital design and standardization of solutions work not as a trendy novelty but as a direct factor in reducing costs and increasing predictability.

a) 3D modeling and element libraries

-

Reduce design time by reusing proven modules;

-

Decrease the number of revisions during approval stages;

-

Allow more accurate estimation of production labor.

b) Basic standardized solutions

Identifying typical models of iconostases and ensembles (for different church sizes) enables:

-

Faster preparation of commercial proposals;

-

Reliance on already established project economics;

-

Lower risk of “beginner mistakes” when entering a new region or project format.

Thus, digital libraries and standardized solutions reduce variability where it does not add value, while leaving creative freedom in areas where the key artistic and spiritual value is created.

6. Family-style management and long-term horizon: linking values and economics

In the craft of church woodcarving, financial sustainability is closely tied to the values of the owners. Family-style management strengthens this connection: the workshop naturally looks at multi-year horizons with prospects for growth and development.

Unit economics in this context is not a dry profit formula but a tool that allows:

-

Making balanced decisions about growth (e.g., opening a second workshop, purchasing new equipment);

-

Building reserves for downturns;

-

Planning the succession of the business to the next generation without debt or critical risks.

Clear project and annual economics reduce emotional strain, freeing space to focus on quality and artistic value, which in the long term only enhances reputation and demand.

Conclusion

The unit economics of a niche church woodcarving workshop is not an abstract theory but a practical tool that allows:

-

Understanding the actual profitability of each project;

-

Identifying which types of orders should be developed and which limited;

-

Planning a project portfolio for a year or several years ahead without illusions or overestimation;

-

Making informed decisions about scaling and investments in equipment and team.

The combination of high-level craftsmanship, family-style management, digital design, and thoughtful unit economics makes even a very narrow niche—such as church woodcarving and iconostases—a sustainable and predictably profitable business. For the market, this means the emergence of players who not only create artistic value but also professionally manage deadlines, budgets, and quality.

References

-

Croll A., Yoskovitz B. Lean Analytics: Use Data to Build a Better Startup Faster. — O’Reilly Media, 2013.

-

Maurya A. Running Lean: Iterate from Plan A to a Plan That Works. — O’Reilly Media, 2012.

-

Industry reviews of creative industries and craft businesses in Europe and Eastern Europe (2019–2024).

-

Methodological materials on managing small manufacturing businesses: unit economics, planning, and cash flow management.

-

Internal data and consolidated case studies from full-cycle church woodcarving workshops (cost structures, pricing approaches, project portfolios).

Author:

Andrei Afanasev

Product manager in the field of Victorian woodcarving