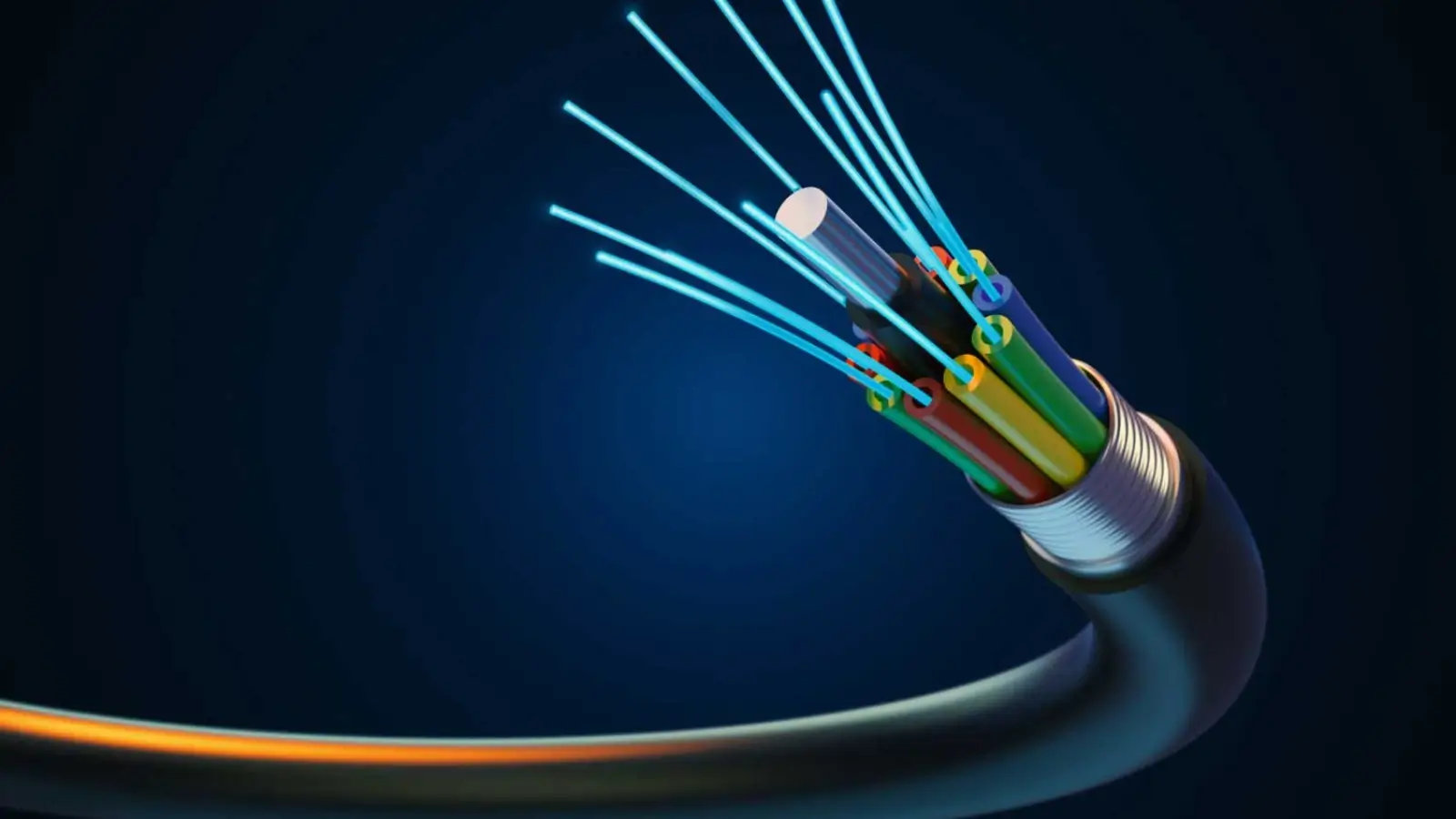

What if Unused Fiber Networks Could Feel Earthquakes?

In recent years, researchers discovered that buried fibre cables can serve as giant sensor arrays to detect seismic activity or environmental change. Could that infrastructure hidden beneath city streets offer new, low-cost environmental monitoring at scale? Enter the potential of dark fiber beyond data transmission.

The Hidden Potential of Unused Infrastructure

Why let fibre sit idle when it can act as living data conduits? Many telecom projects laid down more fibre than needed during infrastructure booms. Now those cables lie unused, in the shadows. Scientists at national labs recently demonstrated that seismic waves passing through soil subtly alter light transmission, and when fibre is instrumented for reflectometry, seismic tremors, ground motion, or temperature shifts become detectable. That suggests that dormant fibre could double as a continuous environmental sensor with vast reach.

From Earthquakes to Water Leakage: Beyond Seismic Uses

Could this technology extend beyond earthquakes? Yes. Researchers envision fibre as distributed sensors for soil moisture, pipeline leaks, permafrost thaw, and even glacier movement detection. As light pulses travel along cables, tiny reflections encode changes in strain or temperature. That means entire lengths—city to city, power corridor to rural highway—become real-time sensor nets. A largely idle infrastructure transforms into a pervasive monitoring system if adopted widely.

How Might Communities Deploy This?

Cities, utilities, researchers, and environmental agencies could lease segments of unused fibre and instrument it with optical time-domain reflectometers (OTDR) or distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) technology. In effect, the same strands that could support high- bandwidth private networks might instead support early warning systems, infrastructure integrity monitoring, or environmental surveillance—even before being “lit” with traditional data traffic. This dual use offers sustainable utility of legacy assets. That vision hinges on access rights, instrumentation costs, and collaboration between public and private sectors.

Using dark fiber as a sensor platform rather than just for telecommunications opens novel possibilities—and the question remains: what if the fiber you once laid for high-speed data becomes your next environmental sentinel?

Drivers and Limitations: What’s Pushing and What’s Holding Back?

Major drivers include growing concern over climate, infrastructure resilience, and natural disaster preparedness. Meanwhile, telecom firms face pressure to monetize excess capacity. However, challenges loom: obtaining permissions to access burial paths, instrumenting cables without affecting future bandwidth use, and integrating sensing analytics at scale. There’s also the cost of retrofitting reflectometry equipment and training operators. Furthermore, many unused fibres may degrade over time or be in inaccessible or private corridors, limiting feasibility.

Are Environment Monitoring Uses More Urgent Than Networks?

With extreme weather and infrastructure failures increasingly common, detecting ground movement, water intrusion, or pipeline leaks could save lives and resources. This raises the question: would repurposing fibre for sensing delay or compete with connectivity expansion plans? On the one hand, unused fibre is rarely prioritized for commercial traffic. On the other hand, demand is growing for 5G, edge computing, and private networks.

Balancing these competing interests poses both technical and policy dilemmas.

What Could a Pilot Project Look Like?

Imagine a metropolitan trench where several unused fibre strands run beneath a river bridge. Instead of leaving them unlit, a local research team partners with the fibre owner to lease them for six months. They deploy portable DAS instrumentation at the ends and capture vibrations caused by heavy trucks, river currents, or minor quakes. The data helps calibrate thresholds for structural warnings or flood detection. If successful, that emboldens wider pilots—perhaps under highways, utility corridors, or rail lines.

Shifting Mindset, Unlocking Value

Rather than letting corridors of dark fibre lie unused, we could treat them as live environmental sensors. The real question: can infrastructure planners, researchers, regulators, and network operators align to repurpose legacy assets for the public good? If so, idle fibre may no longer be dark fiber, and its greatest value could lie not in data throughput, but in data insight about our earth.