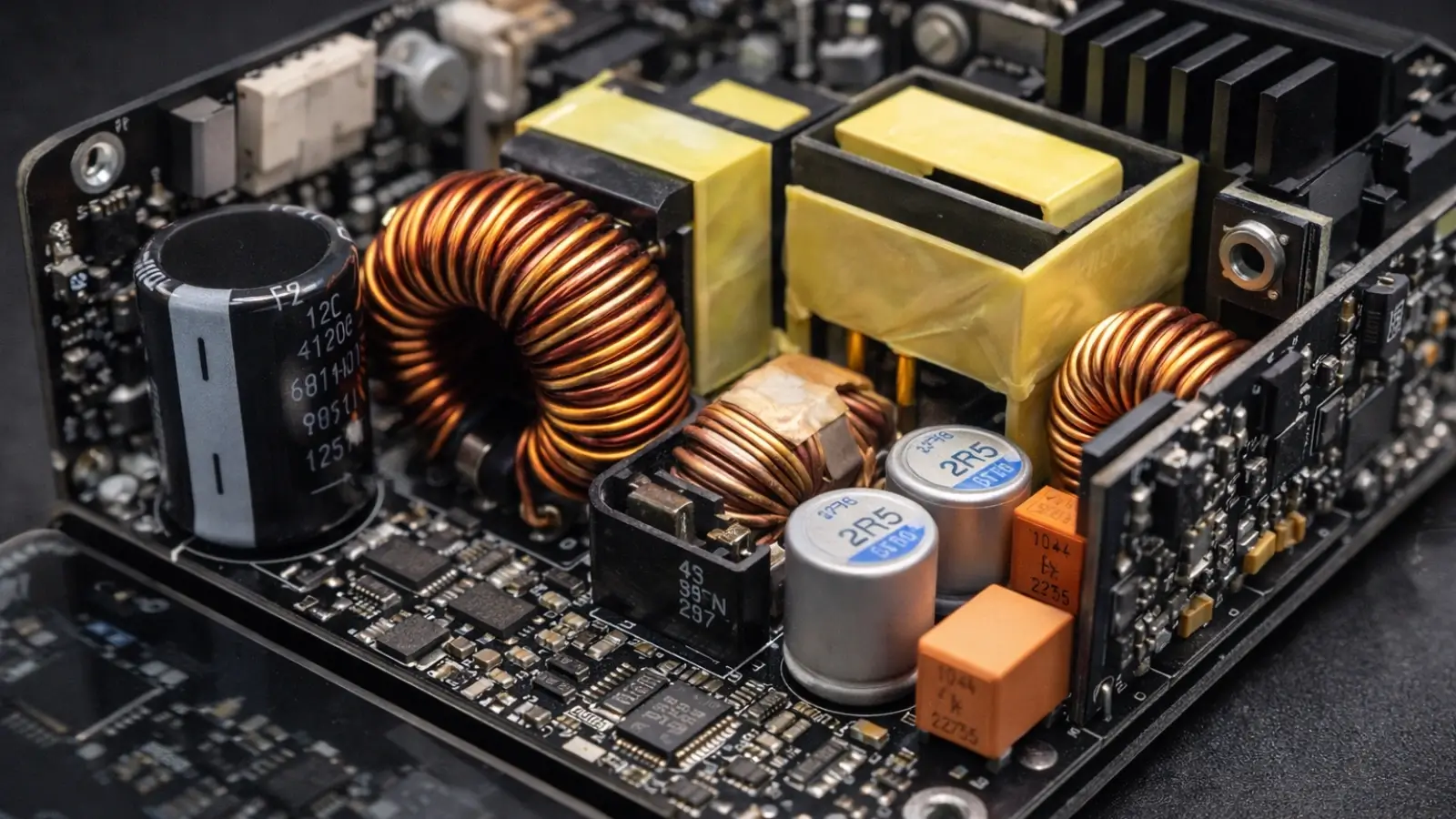

A switching power supply operates by rapidly turning power on and off thousands of times per second, which sounds weird but turns out to be way more efficient than older methods. Instead of continuously regulating voltage and dumping excess energy as heat (like linear power supplies do), switching designs pulse the power flow and use magnetic components to smooth everything out. This approach wastes less energy, runs cooler, and can be made much smaller for the same power output. That's why your modern phone charger is a tiny cube while chargers from 20 years ago were heavy bricks. The switching frequency typically runs between 50 kHz and 500 kHz, fast enough that you can't hear it but slow enough to implement with affordable components.

The Basic Switching Action

At the heart of every switching supply is a transistor (usually a MOSFET) that acts like a super-fast on/off switch. A control circuit drives this transistor, turning it fully on or fully off with nothing in between. When it's fully on, current flows through an inductor or transformer with minimal resistance, so very little power is wasted. When it's fully off, no current flows, so again, no power loss.

The trick is in the timing. By adjusting how long the switch stays on versus how long it stays off (called the duty cycle), you control how much energy gets transferred. A 50% duty cycle means the switch is on half the time and off half the time. Increase that to 70% and you transfer more energy, which raises the output voltage. The control circuit monitors the output constantly and adjusts the duty cycle thousands of times per second to maintain the exact voltage needed.

Why Switching Beats Linear Designs

Linear power supplies regulate voltage by acting like a variable resistor, dropping excess voltage and turning it into heat. If you're converting 12V down to 5V at 1A, you're dropping 7V times 1A, which equals 7 watts of heat. That's a 58% efficient system at best, and you need a big heatsink to dump that heat.

A switching supply doing the same job might achieve 85% to 90% efficiency, wasting only 0.5 to 0.8 watts as heat. That means a much smaller, lighter unit with no fan needed for cooling. This efficiency advantage gets bigger as the voltage difference increases. Converting 120V down to 5V with a linear supply would be completely impractical, but switching supplies handle it easily.

Topologies and Design Variations

Buck converters step voltage down, boost converters step it up, and buck-boost converters can do either. Each topology uses a slightly different arrangement of the switch, inductor, diode, and capacitor, but they all work on the same principle of switching energy transfer.

Isolated designs add a transformer between input and output, which provides electrical separation for safety and allows multiple output voltages from one supply. Flyback converters are popular for low to medium power because they're simple and cheap. Forward converters work better for higher power levels. Full-bridge and half-bridge topologies get used in supplies over 500W where efficiency really matters.

The Control and Feedback Loop

The control IC is basically the brain that makes everything work. It compares the actual output voltage to a reference voltage (usually generated by a precision bandgap circuit) and adjusts the switching to correct any error. This feedback loop operates continuously at speeds matching the switching frequency.

Pulse width modulation (PWM) is the most common control method. The control IC generates pulses where the width varies based on the error signal. More width equals more energy transfer equals higher output voltage. Some designs use frequency modulation instead, varying how often the switch turns on rather than how long it stays on. Newer approaches combine both techniques or use resonant switching to further improve efficiency.

Dealing with Electromagnetic Interference

Here's the downside: all that fast switching creates electrical noise that can interfere with radios, TVs, and other electronics. The sharp edges of the switching waveform generate harmonics that spread across a wide frequency range. That's why switching supplies need careful filtering on both input and output.

Input filters use inductors and capacitors to trap high-frequency noise before it can escape back into the power line. Output filters smooth the switched pulses into clean DC voltage with minimal ripple. Proper PCB layout matters too, with careful attention to trace routing, ground planes, and component placement to minimize radiated emissions. Shielding the entire supply in a metal case helps contain any remaining electromagnetic interference.

Modern Improvements and Efficiency Standards

Recent advances include synchronous rectification, where MOSFETs replace diodes in the output stage, cutting losses significantly. GaN (gallium nitride) and SiC (silicon carbide) transistors can switch faster and handle higher temperatures than traditional silicon, enabling even smaller and more efficient designs.

Efficiency standards like 80 PLUS and Energy Star have pushed manufacturers to optimize their designs. The California Energy Commission sets strict requirements for external power supplies, mandating minimum efficiency at different load levels. These regulations have driven real improvements, with modern supplies routinely hitting 90%+ efficiency where designs from ten years ago struggled to reach 75%.